When people speak of a “doom loop” in the Bay Area, the conversation usually turns toward San Francisco’s well-publicized economic troubles — dwindling downtown foot traffic, shrinking tax revenues, and a growing budget gap accelerated by remote work. The story often goes: declining city services lead to more residents moving away, which worsens the fiscal hole.

But there is another, quieter cycle at play — one that could prove even more transformative for the region’s future. It’s not about commercial vacancies or municipal deficits. It’s about age.

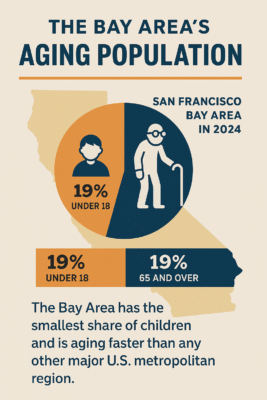

The Bay Area is growing old — and it’s doing so at a pace unmatched by any other major U.S. metropolitan area. While population aging is a global phenomenon, the San Francisco metro area — which spans San Francisco, Alameda, Contra Costa, San Mateo, and Marin counties — now ranks as the third-oldest among the 20 largest metros in the United States, trailing only Miami and Tampa. What’s more, no other major region is aging faster.

From Tech Hub to Gray Hub

Demographic shifts are reshaping the Bay Area in profound ways. Fewer children are being born, the population of residents in their twenties is shrinking, and the proportion of seniors is steadily climbing. By the late 2020s, experts predict that older residents will outnumber children in the region — a milestone many other metros won’t reach until later in the century.

In 2024, less than 19% of the Bay Area’s population was under the age of 18, giving it the smallest share of children among the nation’s 20 largest metro areas. San Francisco County is even more extreme: only 13.5% of its residents are minors, the second-lowest rate among nearly 150 large U.S. counties, surpassed only by Manhattan.

This “graying” of the Bay Area is occurring alongside other challenging trends — skyrocketing housing costs, a reduction in immigration, and shifting cultural attitudes toward family size — all of which threaten the region’s long-term economic vitality.

Urban studies scholar Richard Florida, a professor at the University of Toronto, calls the trend “perhaps the most important change in American society that isn’t getting enough attention.” In high-cost areas like the Bay, he argues, the impact of aging populations is even more acute.

The Numbers Behind the Trend

Even before COVID-19 struck, the San Francisco metro area was among the oldest in the nation. The pandemic accelerated this shift dramatically. From 2020 to 2024, the median age rose from just over 39 years to nearly 41 years — the sharpest increase among the largest U.S. metropolitan areas. For comparison, Houston’s median age is still under 36, and Seattle’s is not yet 38.

In Marin County, the median age now stands at 48, and in Sonoma County it is 44 — placing both among the 25 oldest counties in the country with populations over 250,000. On a neighborhood scale, the variation is striking: areas around UC Berkeley, San Francisco State University, and parts of downtown Oakland remain youthful, while two Berkeley neighborhoods, Thousand Oaks and Northbrae, boast median ages approaching 60. Notably, these are not retirement communities — most residents have lived there for over two decades.

Projections from California’s Department of Finance suggest that by 2055, about half of the residents in the Bay Area’s nine counties will be over the age of 50. In San Francisco and San Mateo counties, the median age is expected to exceed 51 years.

How the Aging Shift Touches Every Corner of Life

The consequences of a rapidly aging population reach far beyond the realm of demographics. They affect everything from the labor market and housing to schools, healthcare, and even nightlife.

1. Education Under Pressure

Public schools are already dealing with declining enrollment — a problem that worsened during the pandemic. As the pool of children shrinks, more schools may be forced to close, creating knock-on effects for educators and for families deciding whether to stay in the region. Even the higher education sector is feeling the shift: while elite institutions like Stanford and UC Berkeley continue to attract applicants, mid-tier universities such as San Francisco State and the University of San Francisco have seen student numbers fall since 2020, eroding the region’s reputation as an educational hub.

2. Economic Ripples

An aging population means fewer working-age adults, which can place “downward pressure” on both labor supply and consumer demand. Businesses that rely on younger patrons — such as bars — are already feeling the pinch. San Francisco bar owners report a dual challenge: older customers are spending less, while younger generations are drinking less altogether.

Jeff Bellisario, executive director of the Bay Area Council Economic Institute, warns that if the pool of young workers shrinks further, the regional economy could stagnate. Skilled labor shortages may deepen, making it harder for businesses to grow or even maintain current operations.

3. Housing Stasis

California’s landmark property tax law, Proposition 13, keeps property tax increases minimal for longtime homeowners. While that’s a boon for those on fixed incomes, it also discourages downsizing or moving, a phenomenon known as the “lock-in effect.” As a result, older residents stay put, reducing the number of homes available for younger buyers and reinforcing the expensive housing market.

For many renters, starting a family becomes the trigger to leave. Space constraints in small, rent-controlled apartments — coupled with high costs for larger units — push parents toward suburban or out-of-state alternatives.

4. Immigration Slowdown

Historically, immigration has helped offset population decline in the Bay Area. But birth rates are falling in key source countries like Mexico and China, and restrictive U.S. immigration policies in recent years — especially during the Trump administration — have slowed the inflow of new residents. Without significant economic changes, experts doubt immigration will be a lasting source of growth for the city.

Not All Sectors Are Struggling

While many industries face challenges from demographic shifts, others are thriving. Businesses catering to older adults are expanding. In South San Francisco, a longevity clinic offers services to clients willing to pay up to $19,000 per year to extend their healthspan. Financial advisors specializing in estate planning and wealth transfer are also in high demand.

These opportunities highlight a broader truth: the “silver economy” — industries serving the needs and preferences of older populations — could become a major growth engine if embraced strategically.

Communities in Transition

The Chronicle’s reporters have documented how the aging trend manifests in different parts of the region:

- In Berkeley, formerly vibrant neighborhoods are evolving into de facto retirement communities of single-family homes.

- In Sonoma County, a city once known for being family-friendly lost 35% of its children in just ten years.

- Across San Francisco, nightlife venues are adjusting to customers who spend less or avoid alcohol altogether.

While the overall picture suggests a clear trajectory toward an older population, these changes are not uniform. University areas, certain urban neighborhoods, and parts of Oakland remain relatively youthful — at least for now.

A Glimpse of America’s Future

The Bay Area is not unique in its demographic direction. All major U.S. metros, and indeed most wealthy nations, are seeing a growing share of seniors and a shrinking share of children. What sets the Bay Area apart is the speed of the shift.

In many ways, the region is a preview of what the rest of the country will face in the decades ahead: pressures on public finances, housing markets shaped by aging-in-place homeowners, labor shortages, and the need for more senior-oriented infrastructure.

Experts agree that adaptation will be essential. This could mean rethinking urban design to make neighborhoods more age-friendly, investing in training for healthcare workers, and ensuring that public transportation serves both seniors and the remaining younger workers efficiently.

Looking Ahead

Stacy Torres, a UCSF assistant professor who studies aging, puts it plainly: “We have to grapple with the fact that this is the future.” Meeting the needs of an older population in a region known for high construction costs and labor shortages will not be easy. The demand for senior housing, home health aides, and supportive community networks will only grow.

Yet neither Torres nor other experts believe this demographic shift will spell the Bay Area’s downfall. Instead, they see it as a challenge that requires creativity, planning, and a willingness to adjust longstanding assumptions about growth and prosperity.

Economist Ted Egan notes that before COVID-19, the number of young, less-educated residents in San Francisco was already declining, while educated young adults moved in for tech jobs. Post-pandemic, even that influx of educated youth has slowed. Without policies that make it easier to raise children in the city — such as affordable housing, accessible childcare, and better family-oriented infrastructure — the trend may be difficult to reverse.

The Bay Area in 2055 and Beyond

By mid-century, half of the Bay Area’s population will be over 50. Schools may be fewer, workplaces may look older, and entire industries will be built around supporting an aging clientele. At some point after 2055, once the baby boomer generation has passed, the median age is projected to decline slightly — but that change is decades away.

Until then, the region’s economic health will depend on how well it can adapt to its new demographic reality. The Bay Area’s aging population will bring both strain and opportunity — from the challenge of keeping classrooms full to the boom in elder care and senior-focused business ventures.

As with many societal changes, the Bay Area is ahead of the curve. The choices it makes now could serve as a model — or a warning — for other regions that will eventually follow the same path.